(This is an English translation of an entry I originally published in Spanish in Nada es Gratis, the leading economic blog in Spanish. Therefore, versión española is here)

A topic often featured in Nada es Gratis is the experimental evidence about different hypotheses or ideas. This is because in the last decades experimental (or behavioral) economics is becoming an important subfield of economics, aiming to understand how we behave in certain situations through an experimental approach. Therefore, readers of Nada es Gratis won’t find it strange that I am talking about this… except for the fact that I am going to discuss experiments with our closest relatives: primates, and in particular chimpanzees. The result is going to surprise you (or maybe not, in fact I’m not surprised by it): we people are dumber than monkeys! The paper that supports (to be sure, in a less sensationalistic manner than me) this conclusion is Chimpanzee choice rates in competitive games match equilibrium game theory predictions, by C. F. Martin, R. Bhui, P. Bossaerts, T. Matsuzawa and C. Camerer. This is Japan-US research team, and prominent among its members is Colin Camerer, one of the most well-known experts in this field (he has just been a plenary speaker at IMEBESS 2015, that took place a few weeks ago in Toulouse, one of the most important conferences on experimental economics originating in the IMEBE series, that was started by Spanish researchers). What interested me most of this work is that they carried out the same experiments with both chimpanzees and humans, so there can be a direct comparison among the behavior of the two species. Before going into the results, it is important to make a few caveats clear, before taking their conclusions at face value. Let us begin by the worst part: the experiment has been done with only three pairs of chimpanzees, and therefore the statistics is not very large. Researchers try to compensate for this repeating the experiments many time, but even so this is an important limitation. It goes without saying that it is very difficult to have many experimental chimpanzee subjects, due to several reasons, the most important one being that there are not that many chimpanzees available: not so many groups have chimpanzees in cautivity (currently called “in sanctuaries“) and when they do they have only a few, and if you want to experiment in the wild it is possible, but it is very complicated logistically. On the other hand, the chimpanzees taking part in the experiment are three couples formed by a mother and her offspring. This could affect the results, although the games the subjects play are not of the cooperation type, and therefore the influence should not be very large. In any event, the authors discuss in their supplementary material that the difference in behavior observed between chimpanzees and humans can not be explained by their kinship relation. But enough of caveats, let us move on to the meat! In the figure below we can see the experimental setup used with the chimpanzees. The blue squares that can be seen on the screen are the two options among which subjects can choose. The games they play are asymmetric, i.e., there are two roles, the matcher and the mismatcher, and they work with several versions of the matching pennies game. The matcher wins when both choose the square on the same side, and the mismatcher wins when they choose the squares on opposite sides. In one of the versions, the side in which both coincide does not matter, while in the other two it is better for the matcher to coordinate in choosing the left side. For the comparison with human subjects, the experiment was also done with students of the universities of Gifu and Kyoto, as well as with people from the Guinea village of Bossou. Both chimpanzees and human subjects played 100 or 200 rounds of the game, alternating roles so all participants were matchers or mismatchers at some point.

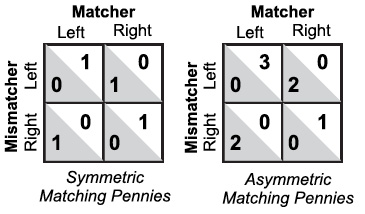

A topic often featured in Nada es Gratis is the experimental evidence about different hypotheses or ideas. This is because in the last decades experimental (or behavioral) economics is becoming an important subfield of economics, aiming to understand how we behave in certain situations through an experimental approach. Therefore, readers of Nada es Gratis won’t find it strange that I am talking about this… except for the fact that I am going to discuss experiments with our closest relatives: primates, and in particular chimpanzees. The result is going to surprise you (or maybe not, in fact I’m not surprised by it): we people are dumber than monkeys! The paper that supports (to be sure, in a less sensationalistic manner than me) this conclusion is Chimpanzee choice rates in competitive games match equilibrium game theory predictions, by C. F. Martin, R. Bhui, P. Bossaerts, T. Matsuzawa and C. Camerer. This is Japan-US research team, and prominent among its members is Colin Camerer, one of the most well-known experts in this field (he has just been a plenary speaker at IMEBESS 2015, that took place a few weeks ago in Toulouse, one of the most important conferences on experimental economics originating in the IMEBE series, that was started by Spanish researchers). What interested me most of this work is that they carried out the same experiments with both chimpanzees and humans, so there can be a direct comparison among the behavior of the two species. Before going into the results, it is important to make a few caveats clear, before taking their conclusions at face value. Let us begin by the worst part: the experiment has been done with only three pairs of chimpanzees, and therefore the statistics is not very large. Researchers try to compensate for this repeating the experiments many time, but even so this is an important limitation. It goes without saying that it is very difficult to have many experimental chimpanzee subjects, due to several reasons, the most important one being that there are not that many chimpanzees available: not so many groups have chimpanzees in cautivity (currently called “in sanctuaries“) and when they do they have only a few, and if you want to experiment in the wild it is possible, but it is very complicated logistically. On the other hand, the chimpanzees taking part in the experiment are three couples formed by a mother and her offspring. This could affect the results, although the games the subjects play are not of the cooperation type, and therefore the influence should not be very large. In any event, the authors discuss in their supplementary material that the difference in behavior observed between chimpanzees and humans can not be explained by their kinship relation. But enough of caveats, let us move on to the meat! In the figure below we can see the experimental setup used with the chimpanzees. The blue squares that can be seen on the screen are the two options among which subjects can choose. The games they play are asymmetric, i.e., there are two roles, the matcher and the mismatcher, and they work with several versions of the matching pennies game. The matcher wins when both choose the square on the same side, and the mismatcher wins when they choose the squares on opposite sides. In one of the versions, the side in which both coincide does not matter, while in the other two it is better for the matcher to coordinate in choosing the left side. For the comparison with human subjects, the experiment was also done with students of the universities of Gifu and Kyoto, as well as with people from the Guinea village of Bossou. Both chimpanzees and human subjects played 100 or 200 rounds of the game, alternating roles so all participants were matchers or mismatchers at some point.  When one faces a game like the one proposed in the experiment, what does game theory recommend us to do? The usual concept to analyze this issue is that of Nash equilibrium, which tells us that players will choose their strategies in such a way that unilaterally changing their choice does not improve their earnings (note that this implies that one has to anticipate what the opponent is going to do). As we do not want to go through the calculation here, allow me to state simply that for the games in the experiment, the matcher is predicted to choose the left or right square with equal probability, whereas the mismatcher will choose one or the other with a probability that depends on the specific payoffs of the version of the game under consideration. This is a complicated scenario, because even if the payoffs the matcher receives change in every version, the prediction for her choice is the same, and on the contrary, for the mismatcher the payoffs are always the same but she must do different things in each version. For reference, the payoff matrices [unknown to the participants] are as follows:

When one faces a game like the one proposed in the experiment, what does game theory recommend us to do? The usual concept to analyze this issue is that of Nash equilibrium, which tells us that players will choose their strategies in such a way that unilaterally changing their choice does not improve their earnings (note that this implies that one has to anticipate what the opponent is going to do). As we do not want to go through the calculation here, allow me to state simply that for the games in the experiment, the matcher is predicted to choose the left or right square with equal probability, whereas the mismatcher will choose one or the other with a probability that depends on the specific payoffs of the version of the game under consideration. This is a complicated scenario, because even if the payoffs the matcher receives change in every version, the prediction for her choice is the same, and on the contrary, for the mismatcher the payoffs are always the same but she must do different things in each version. For reference, the payoff matrices [unknown to the participants] are as follows:

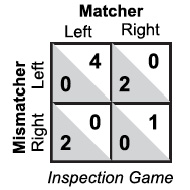

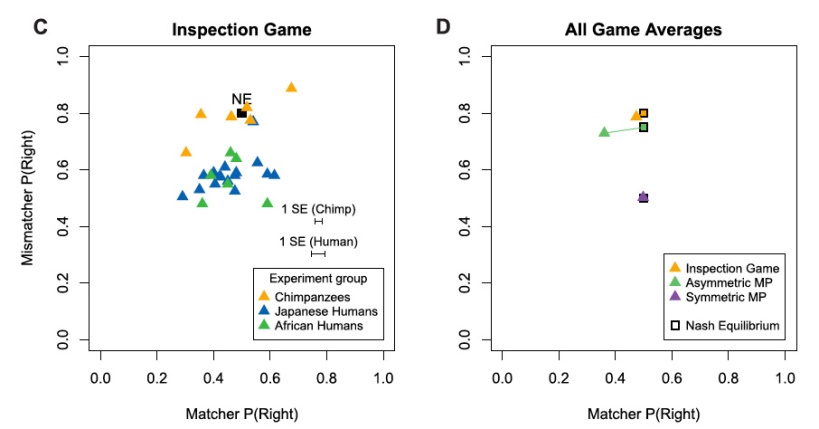

The experimental results are summarized in the following plot:

The experimental results are summarized in the following plot:  The left plot presents the comparison among the frequencies with which players, be they chimpanzees or humans, choose the right square, the horizontal axis corresponding to their role as matcher and the vertical axis to their role as mismatcher, in such a way that every subject is defined by her frequencies in the two roles as a point in these plots. Also shown is the Nash equilibrium prediction for the so-called “inspection game” (lower payoff matrix), the only one that was used with humans. The difference is clear and statistically significant: while chimpanzees choose in both roles with frequencies very close to the Nash equilibrium (particularly as mismatchers), human subjects, either japanese or guinean, behave “less rationally” by choosing the right square as mismatchers far less times than they should. On the other hand, the right plot shows the average of all chimpanzees in all three games, and the agreement between that average and the Nash equilibrium is simply extraordinary. This means that chimpanzees compute Nash equilibria much better than us humans! How can we interpret these results? The authors of the paper advance two hypothesis that are broadly compatible with the observation that chimpanzee choices are much closer to Nash predictions than human ones: Hypothesis 1: the way in which the experiment is set up, i.e., its practical realization, has different effects on chimpanzees and in humans. In relation to this, the authors suggest that more experiments should be tried with experimental setups even closer for the different primates. In the case of the Japanese volunteers, the experimental interface is similar to that used with chimpanzees, but in Guinea experimenters resorted to set bottle caps up or down simultaneously on a table, when they counted to three. However, the authors of the paper believe that this hypothesis is not very probable. To begin with, as we have already said, the kinship relation between the chimpanzee subjects should lead to more cooperative, less competitive behaviors, moving away the observed frequencies from the Nash equilibrium. On the other hand, the learning patterns observed in humans agree very well with other experiments using the same games. Therefore, they claim, the results arising from human subjects are not unusual compared with previous ones. Hypothesis 2: chimpanzees are truly as good as, or even better than, humans in competitive interactions. It is clear that such a strong conclusion needs further research, but authors argue that a cognitive advantage of chimpanzees over humans is likely much in the same way as their physical advantage, particularly in strength and velocity, relevant characteristics in an environment in which there is a very strong hierarchical dominance. Therefore, a cognitive advantage would also be consistent with the difference of environment and behavior. In fact, several experiments have shown that chimpanzees perform better in learning numbers by heart, something that has been related to the idea that in the human brain some tasks are carried out less efficiently because we have “made way” for language, our key competitive advantage. And indeed, language is a crucial factor, and the fact that in this experimental setup human subjects are not allowed to communicate casts doubts on its relevance to real life endeavors. Even so, in a competitive problem as the one we are considering here, language would not help much, although it would help if the aim were to coordinate and cooperate. To conclude, and thanks to my coauthor Antonio Cabrales who pointed it to me, there is an interesting connection with a paper by Ignacio Palacios-Huerta and Oscar Volij, in which they compare professional football players, recruited in first (“La Liga”) and second division teams in the north of Spain, with college students (specifically at Universidad del País Vasco in Bilbao). The result is very clear: Football players do play according to game theory predictions in other competitive games different from those considered here, while students behave significantly differently from the predictions. It seems, then, that being exposed to competitive environments does help subjects to behave “more rationally”, and in this sense college students would be outsmarted by football players. Knowing this, the question arises as to what happens when the comparison involves chimpanzees and football players…

The left plot presents the comparison among the frequencies with which players, be they chimpanzees or humans, choose the right square, the horizontal axis corresponding to their role as matcher and the vertical axis to their role as mismatcher, in such a way that every subject is defined by her frequencies in the two roles as a point in these plots. Also shown is the Nash equilibrium prediction for the so-called “inspection game” (lower payoff matrix), the only one that was used with humans. The difference is clear and statistically significant: while chimpanzees choose in both roles with frequencies very close to the Nash equilibrium (particularly as mismatchers), human subjects, either japanese or guinean, behave “less rationally” by choosing the right square as mismatchers far less times than they should. On the other hand, the right plot shows the average of all chimpanzees in all three games, and the agreement between that average and the Nash equilibrium is simply extraordinary. This means that chimpanzees compute Nash equilibria much better than us humans! How can we interpret these results? The authors of the paper advance two hypothesis that are broadly compatible with the observation that chimpanzee choices are much closer to Nash predictions than human ones: Hypothesis 1: the way in which the experiment is set up, i.e., its practical realization, has different effects on chimpanzees and in humans. In relation to this, the authors suggest that more experiments should be tried with experimental setups even closer for the different primates. In the case of the Japanese volunteers, the experimental interface is similar to that used with chimpanzees, but in Guinea experimenters resorted to set bottle caps up or down simultaneously on a table, when they counted to three. However, the authors of the paper believe that this hypothesis is not very probable. To begin with, as we have already said, the kinship relation between the chimpanzee subjects should lead to more cooperative, less competitive behaviors, moving away the observed frequencies from the Nash equilibrium. On the other hand, the learning patterns observed in humans agree very well with other experiments using the same games. Therefore, they claim, the results arising from human subjects are not unusual compared with previous ones. Hypothesis 2: chimpanzees are truly as good as, or even better than, humans in competitive interactions. It is clear that such a strong conclusion needs further research, but authors argue that a cognitive advantage of chimpanzees over humans is likely much in the same way as their physical advantage, particularly in strength and velocity, relevant characteristics in an environment in which there is a very strong hierarchical dominance. Therefore, a cognitive advantage would also be consistent with the difference of environment and behavior. In fact, several experiments have shown that chimpanzees perform better in learning numbers by heart, something that has been related to the idea that in the human brain some tasks are carried out less efficiently because we have “made way” for language, our key competitive advantage. And indeed, language is a crucial factor, and the fact that in this experimental setup human subjects are not allowed to communicate casts doubts on its relevance to real life endeavors. Even so, in a competitive problem as the one we are considering here, language would not help much, although it would help if the aim were to coordinate and cooperate. To conclude, and thanks to my coauthor Antonio Cabrales who pointed it to me, there is an interesting connection with a paper by Ignacio Palacios-Huerta and Oscar Volij, in which they compare professional football players, recruited in first (“La Liga”) and second division teams in the north of Spain, with college students (specifically at Universidad del País Vasco in Bilbao). The result is very clear: Football players do play according to game theory predictions in other competitive games different from those considered here, while students behave significantly differently from the predictions. It seems, then, that being exposed to competitive environments does help subjects to behave “more rationally”, and in this sense college students would be outsmarted by football players. Knowing this, the question arises as to what happens when the comparison involves chimpanzees and football players…

Pingback: ¿Somos más tontos que los monos? | Nectunt Bitacora